This is the writeup of a presentation given to EGI 2025 Conference in 2025.

EGI has been managing federated infrastructure and delivering services for more than 20 years now. During this time, it has participated in countless infrastructure projects and brought even more services to user communities across Europe and beyond. One key to the long-term stability and maturity of these services is the FitSM standard, which provides requirements and guidelines for managing services in federated environments.

However, EGI has inherited infrastructure and resources from federation partners over the years and continued maintaining this legacy platform without explicitly evolving the methods and practices involved in actually building them.

Whilst FitSM is appropriate and useful for governing and managing services at a mature stage of development, it doesn’t provide the opinions, guidelines, or patterns for quickly ramping up and iterating the development of infrastructure components themselves—or services deployed within them.

This has been addressed in environments where fast iteration towards high-quality services creates competitive advantage. One need only refer to DevOps practices for a good frame of reference. A shorthand introduction to this article might be:

The key for making change fast is DevOps, whilst the key for managing mature services is FitSM

Lack of constraints leads to lack of function

The collaboration, observation, and fast feedback patterns of DevOps allow us to reach a position where system governance becomes feasible more quickly. At that point, we can start extracting value from the FitSM standard with its clear requirements.

In our context, software systems are built and delivered by federations—independent teams under separate domains. There are so many tools available in every phase of the software development lifecycle that independent teams almost certainly evolve different toolkits. This creates a situation where the freedom to select tools for local DevOps optimisation ends up frustrating efforts to globally optimise FitSM governance.

Since each team delivers with different toolkits, implementing machine-readable procedures becomes prohibitively complex. The only tool truly shared by all teams is human language. FitSM requirements are then implemented by adopting this lowest common denominator—human-readable processes, procedures, and policies1.

Furthermore, procedures tend to be intentionally vague, given the opacity across domain boundaries. Teams in one area lack visibility into another’s workings and must describe procedures in terms of generic interfaces rather than specific actions. Whilst this has benefits—abstract interfaces allow tooling to change without altering procedures—there are better ways to achieve this whilst providing superior system understanding.

Patterns impose constraints

This complexity problem has been encountered repeatedly in enterprises large and small. It’s a consistent hurdle that becomes inevitable once a certain scale is reached. The boundary between distinct domains is analogous to the traditional boundary between development and operations concerns.

Just as we realised that better dev-ops collaboration could lead to superior overall outcomes, there were plenty of ways to do it “wrong”. The frustration from lacklustre DevOps adoption returns led some in the industry to consider what patterns or antipatterns were present. This approach led to “Team Topologies”2—a guide to identifying which interaction model suits a given environment.

Emerging from this research was the concept of a “platform”—an abstract set of functions which, when organised together, allow software delivery teams to perform tasks with less cognitive load, fewer dependencies, and faster feedback. A few iterations later, we arrive at a semi-codification of this pattern: platform engineering.

Platform engineering is the practice of building platforms3 designed for delivery. Another way to think of this: a platform is “the product that helps us deliver services to our customers”. This links our fast-flow, fast-feedback, tool-integration DevOps world with our quality-oriented, requirements-first, process-aligned service management FitSM world.

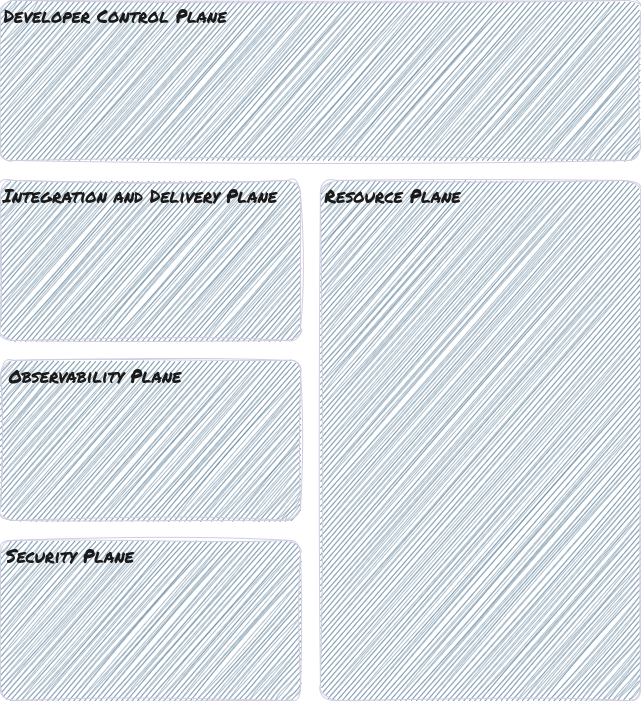

The platform engineering pattern helps various domains adopt consistent patterns, even without overall consensus on specific tooling. It organises tools according to their function and position in the software delivery lifecycle, identifying certain “planes”:

-

Developer Control Plane: Contains all necessary tooling for developers to build applications. This includes version control for applications and the platform infrastructure’s source code. In mature cases, it includes an internal service catalogue and API gateway that developers use to identify reusable components and avoid duplication.

-

Integration and Delivery Plane: Work from the Developer Control Plane flows here. This includes continuous integration (CI) pipelines, artifactories, and continuous deployment (CD) pipelines. A crucial component is the platform orchestrator, which deploys new artefacts into deployment environments based on platform definitions, configuration constraints, and policies.

-

Resource Plane: Contains the actual operating environment for services offered to customers. This is the traditional “Ops” part of DevOps, bound to reliability, security, and cost objectives. It includes all environments: testing, staging, and production.

-

Observability Plane: Monitors all platform components and provides the bedrock for feedback. It collects metrics from platform components and services deployed in the Resource Plane, alerting based on defined service level objectives. It also aggregates logs and traces across the platform.

-

Security Plane: Responsible for declaring, enforcing, and supporting security and safety across the platform and its workloads.

We’re still hiding tooling complexities behind the “plane” abstraction, but at least we now have a common model across different domains.

Overcoming boundaries

The platform engineering pattern tames DevOps complexity, but we’re still left with organisational boundaries inherent in federations. Have we improved the situation by adopting platforms, or created more work since every team must now build one?

Organisational boundaries won’t simply disappear. Even though our platform describes interaction patterns, we still need to implement those interactions. Code commits must flow through CI, workload definitions need auditing, securing, and delivery to various resource planes across boundaries (i.e., heterogeneous toolkits).

The question becomes:

How can we build a platform whilst respecting organisational boundaries?

Given that platform components, or entire planes, may be provided by different organisations:

How can I consume platform component services or expose my component’s services across opaque organisational boundaries?

This may be analogous to the “Bezos API Mandate”4. To paraphrase5:

- All teams will expose their data and functionality through service interfaces

- Teams must communicate through these interfaces

- No other form of interprocess communication is allowed

- Technology choice doesn’t matter

- All service interfaces must be designed to be externalisable

Wouldn’t it be brilliant if all platform functionality needed to deliver services to users were exposed as APIs?

Workflows in platforms vs tools

Most toolkit tools do expose APIs for external consumption. The problem is that we’ve deliberately avoided referencing explicit tooling in our platform pattern. When platforms are eventually created using actual tools, and the only way to use those tools in delivery workflows is via their specific APIs, we’re back to the complexity we tried to address.

We’d have to integrate with numerous APIs and account for countless specific configurations to use the platform. This clearly isn’t an improvement!

Event-driven architectures

Tightly-integrated end-to-end workflows for change management, release, deployment, and monitoring—i.e., all service management system requirements—are thus doomed. They’re either too narrow in scope (single org or team), too costly to implement (too many different tools and APIs), or too expensive to maintain (tools change, requiring ongoing API integration work).

But what if we didn’t need end-to-end workflows? An alternative would be taking an event-driven system view. This allows writing procedures as combinations of specific events, actors, and actions:

In this scenario, actors subscribe to events, and know what to do when a given event occurs – they take the relevant action. These actions can be codified accordingle, whilst the SMS policy defines actors. What remains is deciding the triggering event and determining how actors are notified.

This is where the CDEvents specification comes in. As we’ll see in the next post, common event specification in software systems will allow us to build tool-agnostic platforms for delivering software systems to customers across organisational boundaries.

This will be discussed in Part II, where we dive into the CDEvents specification and show how it can solve our complexity and integration problems.

Footnotes and References

-

Perhaps one day large language models (LLMs) will make human language a valid interface for implementing machine-readable workflows, but we’re most definitely not there yet. ↩

-

Skelton, M., & Pais, M. (2019). Team topologies: organizing business and technology teams for fast flow. It Revolution. ↩

-

The term “platform” appears repeatedly in this article. To be clear, we’re referring to the same platform that Evan Bottcher discusses in What I talk about when I talk about platforms ↩

-

The only attribution I could find was Steve Yegge’s second-hand, accidental post. It has been almost lost to time thanks to Google+’s shutdown (irony of ironies). ↩

-

This isn’t faithfully reproduced—I’ve edited and omitted several parts. See the original for greater context. ↩